The third and last machine-made scent for your nose to encounter is from this next painting,

A Saint of the Eastern Church by Simeon Solomon.

The obvious choice might be that twig of fragrant myrtle flowers, often seen as a symbol of purity, innocence and hope. It is a dainty accompaniment to the incense burner that gives off a very particular odour. In fact, it's a heady combination: an unmistakable church smell of incense, candles, the saint's brocade clothing as well as the myrtle.

We learn at the start of the show that in 1855, the Victorian physiologist Alexander Bain described vivid multisensory experiences as the normal, healthy response to imagery. A picture of flowers, he argued, "gives an agreeable suggestion of the fragrance," because it would trigger memories of smelling actual flowers, setting into play the same muscles and nerve tracks. With their gorgeous flowers, censers of incense and vials of scented poison, Victorian Aesthetic paintings seem designed to prompt such an reaction, according to curator Dr Christina Bradshaw.

Of course, not everything is sweet smelling: Scientists had already been suggesting that the River Thames, the source of drinking water for many residents of London, carried numerous unseen dangers that were blamed for outbreaks of cholera and other diseases.

A humorous Punch cartoon of 1850,

A Drop of London Water, depicts some of the nasties that a Victorian satirist feared might lurk in the Thames, suggesting that under a microscope a "myriad of minuscule yet hideous forms" could be seen. In place of the algae and protozoans that scientists were discovering, Punch uncovered town councillors, church wardens, undertakers, bailiffs and slopsellers in the water. Satire doesn't change much....

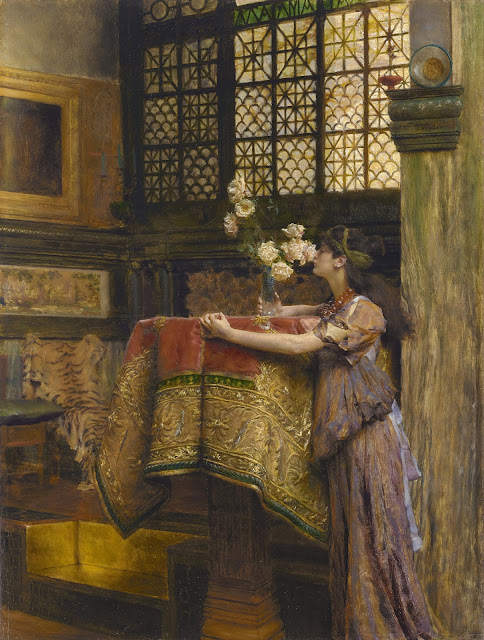

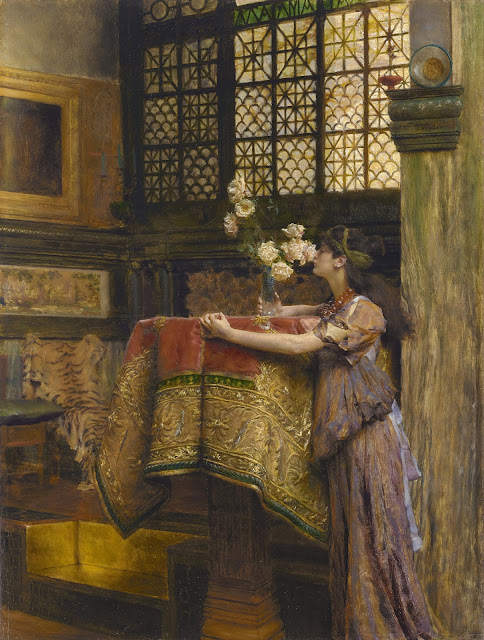

But let's not linger over the malodorous and go back to the fragrant flower girls. Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema posed his subject almost embracing the vase of flowers In My Studio. The work is a wonderful example of Victorian interest in interior decoration and was typical of Symbolist paintings from about 1870 to 1915 in which scent became a way to convey mood and mystery. Writers at the time described scent as arousing for women, linking fragrance to desire, the caption explained.

.jpg)

Women smelling flowers became a popular theme. Although more of them were becoming independent and career-focused, they were shown on canvas as flower-like, passive and still. Contemporary theories suggested females had a stronger sense of smell and were more painfully and pleasurably affected by it than men.

This next girl, in her long simple white dress, looked to us so childlike and innocent as she dreamily put her nose to the posy in a vase on a shrine. But in the mid-1890s, when it was painted by John William Waterhouse, a critic branded her as "rather sensual and not so pure as she ought to be". And that stooping to smell roses was "out of keeping with the religious reverence of a shrine".

There's no shortage of flowers in

Lilium Auratum by John Frederick Lewis. The viewer can't but sense the intense heady odour of the lilies combined with the more delicate perfume of all the roses. The two Eastern-looking figures, busy selecting their bouquet from a great variety of flowers, are far from the usual depictions of harem women reposing or dancing. Lewis's canvas recalls Victorian ideas of Eastern sensuality, luxury, wealth and abundance.

.jpg)

Though, as we saw in a

previous exhibition at the Watts Gallery a few years ago, Lewis tended to concoct such Oriental scenes in his garden in Walton-on-Thames.

And finally, to a dark glen in Psyche Opening the Golden Box, a story from Greek mythology which highlights a terrible problem facing Victorian society. The Goddess of the Soul, Psyche, defies a warning not to open the casket and in doing so releases a cloud that sends her into a deep sleep. Waterhouse depicts the sleeping spell as a vapour in keeping with Victorian research on the drug-like effects of strong smells. The mauve flowers in the foreground are clearly poppies alluding to the devastation of opium addiction and use of laudanum, an opium tincture, as a sleeping aid.

And so we end as we began, with a flower not known for its scent.

Practicalities

Scented Visions: Smell in Art 1850-1914 is on at the Watts Gallery in Compton, near Guildford, until November 9. It's open daily from 1030 to 1700. Full-price tickets to the Watts Gallery site cost £19.80 including Gift Aid, £18 without (prices drop slightly in November). However, as well as the exhibition, that gets you into the collection of paintings and sculpture by Watts himself, a gallery featuring the art of

Evelyn De Morgan and the pottery of her husband William, and the Watts home at

Limnerslease across the road. Tickets can be bought online

here. On the first Wednesday of every month, admission is on the basis of pay if and what you can. Just down the road, with free entry, is the spectacularly decorated

Watts Cemetery Chapel, the last resting place of GF and his second wife Mary.

Compton is just off the A3 if you're travelling by car. It's easy to get to by public transport: Take a train to Guildford, from where the

46 bus runs direct to the gallery once an hour Mondays to Saturdays, taking just over 10 minutes. On a nice day, it's a pleasant walk from Guildford on an easy route in a little over an hour via the River Wey and then the North Downs Way, which goes right past the Watts Gallery.

Images

GF Watts (1817-1904), Ellen Terry (Choosing), 1864, National Portrait Gallery, London. © National Portrait Gallery

John Everett Millais (1829-1896), The Blind Girl, 1856. Birmingham Museums Trust. Photo by Birmingham Museums Trust, licensed under CC0

Simeon Solomon (1840-1905), A Saint of the Eastern Church (formerly called A Greek Acolyte), 1867-68, Birmingham Museums Trust. Photo by Birmingham Museums Trust, licensed under CC0

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912), In My Studio, 1893, The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

John William Waterhouse (1849-1917), The Shrine, 1895, Private collection

John Frederick Lewis (1804-1876), Lilium Auratum, 1871, Birmingham Museums Trust. Photo by Birmingham Museums Trust, licensed under CC0

John William Waterhouse, Psyche Opening the Golden Box, 1903, Private collection

,%201864,%20oil%20on%20strawboard%20mounted%20on%20Gatorfoam,%2047.2%20x%2035.2cm%20%C2%A9%20National%20Portrait%20Gallery%20(wecompress.com).png)

.jpg)

,%201867%20-%201868,%20watercolour%20and%20gum%20over%20pencil,%20on%20paper,%2045.2%20x%2032.8cm.%20%C2%A9%20Birmingham%20Museums%20Trust.jpg%20(wecompress.com).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment