She was a highly successful artist in 17th-century Brussels, creating the sort of paintings you might have seen from Rubens or Van Dyck, but then she vanished from art history. It's only very recently she's been rescued from obscurity, her pictures rightfully reattributed. Michaelina Wautier comes to the Royal Academy in London on March 27 from the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, offering the first opportunity to encounter her work on a large scale. On till June 21. And while we're on the theme of new discoveries, we've made quite a few at the Dulwich Picture Gallery down the years. The latest arrival there is a completely unknown name to us, from the Baltic: Konrad Mägi (1878-1925), described as a pioneer of Estonian modernism. More than 60 of his works are being shown in the UK for the first time in an exhibition that runs from March 24 to July 12. No introduction is needed for David Hockney, and he's taking over the Serpentine Gallery on March ...

Albrecht Dürer: one of the great names of Renaissance art. His printmaking secured the man from Nuremberg lasting fame across Europe in his own lifetime, with his AD monogram becoming a pioneering symbol for quality and authenticity.

In his native Germany, where Dürer is one of the key figures in the country's cultural history, we've seen some wonderful and exhaustive -- if exhausting -- exhibitions of his work, particularly at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg itself. Dürer's Journey's: Travels of a Renaissance Artist at the National Gallery in London doesn't approach those heights; for one thing, there aren't really that many of Dürer's greatest hits -- you won't be seeing his Hare, or his Rhinoceros -- and while there are some fascinating woodcuts and engravings by the German, we got the impression that his paintings here were a little bit overshadowed by the work of other artists on show -- Giovanni Bellini and Quinten Massys, to name but two.

The idea behind this exhibition is to present Dürer's work through the prism of the journeys he made from Nuremberg. He first travelled across the Alps to Venice in the summer of 1494 and undertook a second trip a decade or so later. He then went to the Low Countries in 1520-21. That later journey, mainly to Flanders, gets rather more coverage in this show than the stays in Venice; the National Gallery exhibition follows on from one at the Suermondt-Ludwig Museum in Aachen last year that focused on Dürer's visit there.

An outstanding Dürer painting on show from the Venice period is this one, a Madonna and Child from the National Gallery of Art in Washington. It's rich colouring is indebted to Bellini, one of the greatest of Venetian artists, a painter also known for his backgrounds and landscapes and someone who knew a thing or two about Madonnas.

Dürer wrote on his second trip to Venice that Bellini was "very old, but he is still the best painter of them all."There's a very late Bellini on show in this section, the National's own Assassination of St Peter Martyr. It's a breathtaking painting, the violence of the killing of the Dominican friar by members of a heretical sect echoed in the actions of the woodsmen behind.

But it also shows that the exchange of ideas was mutual. Not only did Bellini influence Dürer, the German artist inspired the Venetian as well. A bullock cropped by the left edge of the painting suggests space and movement beyond the frame. Nearby hangs an early Dürer engraving, The Prodigal Son, using exactly the same device.

But it also shows that the exchange of ideas was mutual. Not only did Bellini influence Dürer, the German artist inspired the Venetian as well. A bullock cropped by the left edge of the painting suggests space and movement beyond the frame. Nearby hangs an early Dürer engraving, The Prodigal Son, using exactly the same device.

There's a charming little painting in the Venice section by Dürer of A Lion, made in 1494, but it's a rather unconvincing-looking wild beast.

This lion appears to be an adaptation of heraldic representations of the animal, the curators tell us, owing more to medieval illustrated manuscripts. Dürer was probably unable to study a real lion until he went to the Low Countries more than a quarter of a century later and drew animals in the zoos in Brussels and Ghent. Some of those fine sketches can be seen later on.

This lion appears to be an adaptation of heraldic representations of the animal, the curators tell us, owing more to medieval illustrated manuscripts. Dürer was probably unable to study a real lion until he went to the Low Countries more than a quarter of a century later and drew animals in the zoos in Brussels and Ghent. Some of those fine sketches can be seen later on.

Dürer's big triumph on his second trip to Venice was the creation of an altarpiece for the German merchants' church there, San Bartolomeo, intended to show Venetian competitors that he was a master of colour as well as black-and-white prints. We don't get to see the damaged original of The Feast of the Rose Garlands, which is now in Prague, but there is on show a copy made a century later, on loan from Vienna.

One of those German merchants whose faces appear in the altarpiece is Burkhard of Speyer, and his portrait is included in this exhibition. Dürer adopts the tight head-and-shoulders format favoured by Venetian painters. It's a strongly expressive portrait with its pronounced shadows, one of Dürer's best in this show.

There are a fair number of portraits in the sections on Dürer's visit to the Low Countries. Quite a lot of them are by other artists who were working there at the time, such as Massys, Jan Gossaert and Lucas van Leyden; some are from the National's own collection, though by no means all. Dürer's generally sober portraits contrasted strongly with those of his Netherlandish contemporaries, who tended to favour illusionistic backgrounds.

One of the star works in this room is indeed Quinten Massys' picture of a star of the period -- the eminent philosopher and theologian Erasmus of Rotterdam.

Erasmus is such a well-known face; there's no mistaking him, and the Massys likeness is backed up by Hans Holbein's portraits of the great man. Dürer drew Erasmus too, and eventually produced an engraving; it's a bit of a shock to find that apart from the distinctive nose it looks like someone else entirely. Having said that, it's the drawings and engravings that are the real highlights of Dürer's work in this exhibition, rather than paintings. There are some superb drawings from the Low Countries of locals, scenes and animals in the zoo; on show behind glass, sadly for us, as the reflections mean they tend not to photograph very well.

Dürer took his work to the Netherlands to sell; items such as this complex and highly detailed engraving of The Knight, Death and the Devil, with its beautiful depictions of the sheen on the knight's armour, the horse's coat and the loping dog's shaggy fur, as well as the fantastic figures of death and the demon.

Now, we often have the feeling that exhibitions in the National Gallery's Sainsbury Wing seem to run out of steam a bit before they reach the end (or perhaps we don't pace ourselves properly). Nearly always, the items on display in the penultimate room are not quite so thrilling, and this Dürer show is no exception. You can feel yourself physically flagging, partly because you don't want to miss any of the detail that Dürer crammed in to so much of his output.

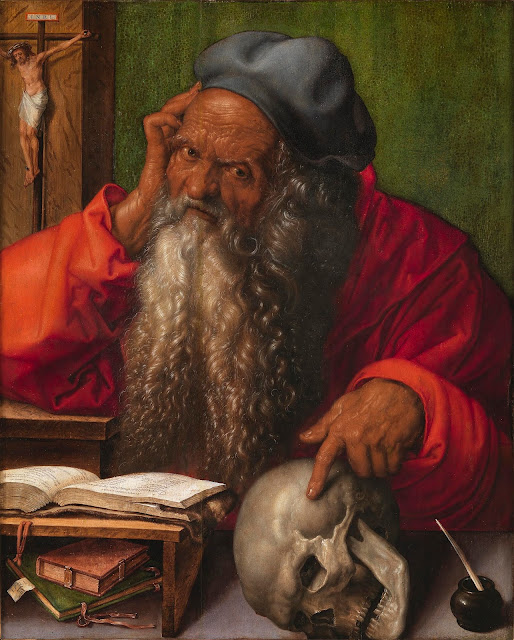

Pride of place in the final room is given over to a Dürer painting that's quite different from the norm; earlier in the show we've seen his engraving of St Jerome in his Study, with a full range of the saint's traditional attributes, including the lion from whose foot he removed a thorn, a skull and the cardinal's hat on a wall. A prime example of Dürer's sharp observation and precise depiction of elements such as the individual panes of glass in the window and the shadows they cast.

The Saint Jerome Dürer created in Antwerp for a Portuguese merchant, though, has no lion and no cardinal's hat. His eyes are not on his book, but fixed on the viewer, his finger on the skull that's the symbol of the transience of life. He seems worn out.

So what to make of this show? There's undoubtedly a lot to see but we have to admit we found it just a bit underwhelming; there's very little wow factor that will make it last long in our memories. There are other, more exciting exhibitions that you can see right now. Practicalities

Dürer's Journey's: Travels of a Renaissance Artist continues at the National Gallery in London until February 27. It's open daily from 1000 to 1800, with lates on Fridays to 2100. Standard admission is £20, and you can book online here. Don't forget your headphones, earbuds, AirPods or equivalent as there is an excellent free audio guide to play through your smart device. We spent well over two hours in this show; it's quite crowded in there and many exhibits are smallish, so factor in a bit of shuffling around and waiting for a view. The National Gallery is on the north side of Trafalgar Square, just a couple of minutes from Charing Cross or Leicester Square stations on the rail and Underground networks.

Images

Albrecht Dürer, A Lion, 1494, Hamburger Kunsthalle. © Photo Scala, Florence/bpk, Bildagentur für Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte, Berlin/Photo: Christoph Irrgang

Giovanni Bellini, The Assassination of St Peter Martyr, about 1505-07. © The National Gallery, London

Albrecht Dürer, Burkhard of Speyer, 1506, Lent by Her Majesty The Queen, Royal Collection Trust. © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

Quinten Massys, Desiderius Erasmus, 1517, Lent by Her Majesty The Queen, Royal Collection Trust. © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

Albrecht Dürer, The Knight, Death and the Devil, 1513, The Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Albrecht Dürer, Saint Jerome, 1521, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon. © Instituto Portugues de Museus, Ministério da Cultura, Lisbon

Comments

Post a Comment