This year marks the 100th anniversary of the death of Claude Monet, the Impressionist par excellence, and unsurprisingly there's no shortage of Monet-related exhibitions, particularly in France, to mark the occasion. So if you want to fill 2026 with luminous, atmospheric landscapes and dreamy water lilies, we have some dates for your diary. We'll take the big shows in chronological order, which means crossing the border into Germany for the first of them. We can vouch for it that Monet on the Normandy Coast: The Discovery of Etretat at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt is an excellent exhibition; we saw it in Lyon late last year. Monet was fascinated by the chalk cliffs around the fishing village of Etretat with their eroded formations -- creating bizarre doors and needles -- and he produced a series of pictures showing the light and weather effects on the land and sea. There are 24 works by him on display; Monet's the star, but you'll also find dozens mo...

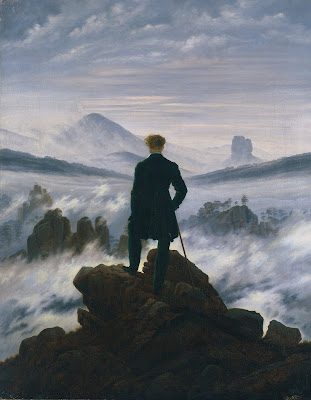

It's one of the most iconic of all German paintings, and it's one of the star attractions of a show in Berlin that's steeped in the Romanticism of the early 19th century.

The picture is Caspar David Friedrich's Wanderer above the Sea of Fog. A curly-haired man in a dark green suit is seen from behind, standing atop a rocky outcrop with his walking stick and gazing down into an eerie landscape in which mists swirl around mountain tops.

The exhibition is Wanderlust: From Caspar David Friedrich to Auguste Renoir in Berlin's Alte Nationalgalerie, looking at the wanderer as a central theme in 19th-century art across Europe. The museum has a fine Friedrich collection itself, but the curators have pulled in some splendid paintings from across the continent. The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog has made the short trip from Hamburg.

The story starts with the discovery of nature, even at its wildest, as a phenomenon to be explored close up in the 18th century. In Jakob Philipp Hackert's Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 1774, you can follow the gash of red molten lava up and discern a tiny trio who have climbed to examine the phenomenon from as close as possible. Look a little harder and you discover yet more thrill-seekers climbing the mountain to join them.

As with fire, so with ice, and paintings by Swiss artists Caspar Wolf and Heinrich Wüest depict the huge power of glaciers and man's smallness in their presence. How startling these images must have appeared to many of their contemporaries who had never travelled.

But the walkers of today will feel at one with a number of other works. Anyone who's ever been up a mountain in Scotland will find familiar weather in Jean-Bruno Gassies' Scottish Landscape, the mist swirling around even as breaks in the cloud show off the view of the lochs below. Hans Thoma's Taunus Landscape captures that moment of pleasure when you take in the view of the panorama from a high vantage point.

But it's not just about the surroundings; it's about the journey. A room devoted to the topic illustrates how so often the wanderer's way was an allegory for the passage through life. In the early 20th century, Emil Nolde portrayed this solitary walker on a winding path through a snowy landscape in Winter.

In Ludwig Richter's Crossing the Elbe at the Schreckenstein, the traveller's evening boat trip across the river symbolises both a farewell to the day, and to life. Ferdinand Hodler's Tired of Life shows an old man at the end of his journey, cloaked in dust.

This is, admittedly, all a bit Germanic, but artists from other nations also eagerly embraced the subject of walking in the countryside as a reaction to the faster pace of life and changes in a society in which people travelled increasingly by stagecoach or by train. Some are unfamiliar names to most of us: The Dane Jorgen Roed depicts An Artist Resting by the Roadside, possibly himself, sunk in contemplation. The Russian Ivan Kramskoy shows us his fellow artist Ivan Shishkin, having a smoke before settling down to paint.

The highlight in this section of the show, though, comes from Gustave Courbet. The Meeting or Bonjour Monsieur Courbet presents the painter walking through the country, being greeted by his wealthy patron Alfred Bruyas, who doffs his hat, while his servant bows his head. It's the painter as hero, on a monumental scale. He's the only one casting a shadow. The critics hated it.

Of course, this was the 19th century, and hitting the open road was a male preserve. But as the decades wore on, women did begin to make an appearance in the countryside, perhaps not on hikes, but what might be termed strolls or promenades. It's a classic Impressionist subject, and one such example in Berlin is Auguste Renoir's Path Leading through Tall Grass from the Musée d’Orsay. The vegetation shimmers in the dappled light, the dresses, hats and parasols of the women and children are blurs of colour snaking down the canvas.

Two decades on, by the 1890s, emancipation has taken a step further. The woman in Richard Riemerschmid's In the Countryside wears a less constricting corsetless dress as she walks, not on a path, but through open meadowland. The painting has a much more illuminating title in German: In freier Natur, literally In Free Nature.

And by the early years of the 20th century, a woman could take up a monumental role to rival Friedrich's wanderer above the mist. Jens Ferdinand Willumsen's Mountain Climber is the picture that you see as you enter and leave the show.

This is a big exhibition, with more than 120 paintings. German galleries do like to be exhaustive, but that sometimes means exhausting, and there are some less interesting sections here where you feel the curators could have been a bit more selective. As on so many rambles, another few well-placed benches and a refreshment stop would have been welcome. But all in all, this is a very enjoyable show. Do see it if you're in Berlin.

Richard Riemerschmid, In the Countryside, 1895, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich. (c) Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau München

Jens Ferdinand Willumsen, A Mountain Climber, 1912, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen. (c) Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018

The picture is Caspar David Friedrich's Wanderer above the Sea of Fog. A curly-haired man in a dark green suit is seen from behind, standing atop a rocky outcrop with his walking stick and gazing down into an eerie landscape in which mists swirl around mountain tops.

The exhibition is Wanderlust: From Caspar David Friedrich to Auguste Renoir in Berlin's Alte Nationalgalerie, looking at the wanderer as a central theme in 19th-century art across Europe. The museum has a fine Friedrich collection itself, but the curators have pulled in some splendid paintings from across the continent. The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog has made the short trip from Hamburg.

The story starts with the discovery of nature, even at its wildest, as a phenomenon to be explored close up in the 18th century. In Jakob Philipp Hackert's Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 1774, you can follow the gash of red molten lava up and discern a tiny trio who have climbed to examine the phenomenon from as close as possible. Look a little harder and you discover yet more thrill-seekers climbing the mountain to join them.

As with fire, so with ice, and paintings by Swiss artists Caspar Wolf and Heinrich Wüest depict the huge power of glaciers and man's smallness in their presence. How startling these images must have appeared to many of their contemporaries who had never travelled.

But the walkers of today will feel at one with a number of other works. Anyone who's ever been up a mountain in Scotland will find familiar weather in Jean-Bruno Gassies' Scottish Landscape, the mist swirling around even as breaks in the cloud show off the view of the lochs below. Hans Thoma's Taunus Landscape captures that moment of pleasure when you take in the view of the panorama from a high vantage point.

But it's not just about the surroundings; it's about the journey. A room devoted to the topic illustrates how so often the wanderer's way was an allegory for the passage through life. In the early 20th century, Emil Nolde portrayed this solitary walker on a winding path through a snowy landscape in Winter.

In Ludwig Richter's Crossing the Elbe at the Schreckenstein, the traveller's evening boat trip across the river symbolises both a farewell to the day, and to life. Ferdinand Hodler's Tired of Life shows an old man at the end of his journey, cloaked in dust.

This is, admittedly, all a bit Germanic, but artists from other nations also eagerly embraced the subject of walking in the countryside as a reaction to the faster pace of life and changes in a society in which people travelled increasingly by stagecoach or by train. Some are unfamiliar names to most of us: The Dane Jorgen Roed depicts An Artist Resting by the Roadside, possibly himself, sunk in contemplation. The Russian Ivan Kramskoy shows us his fellow artist Ivan Shishkin, having a smoke before settling down to paint.

The highlight in this section of the show, though, comes from Gustave Courbet. The Meeting or Bonjour Monsieur Courbet presents the painter walking through the country, being greeted by his wealthy patron Alfred Bruyas, who doffs his hat, while his servant bows his head. It's the painter as hero, on a monumental scale. He's the only one casting a shadow. The critics hated it.

Of course, this was the 19th century, and hitting the open road was a male preserve. But as the decades wore on, women did begin to make an appearance in the countryside, perhaps not on hikes, but what might be termed strolls or promenades. It's a classic Impressionist subject, and one such example in Berlin is Auguste Renoir's Path Leading through Tall Grass from the Musée d’Orsay. The vegetation shimmers in the dappled light, the dresses, hats and parasols of the women and children are blurs of colour snaking down the canvas.

Two decades on, by the 1890s, emancipation has taken a step further. The woman in Richard Riemerschmid's In the Countryside wears a less constricting corsetless dress as she walks, not on a path, but through open meadowland. The painting has a much more illuminating title in German: In freier Natur, literally In Free Nature.

And by the early years of the 20th century, a woman could take up a monumental role to rival Friedrich's wanderer above the mist. Jens Ferdinand Willumsen's Mountain Climber is the picture that you see as you enter and leave the show.

This is a big exhibition, with more than 120 paintings. German galleries do like to be exhaustive, but that sometimes means exhausting, and there are some less interesting sections here where you feel the curators could have been a bit more selective. As on so many rambles, another few well-placed benches and a refreshment stop would have been welcome. But all in all, this is a very enjoyable show. Do see it if you're in Berlin.

Practicalities

Wanderlust is on at the Alte Nationalgalerie on Berlin's museum island in the centre of the city until September 16. It's open from 1000 to 1800 Tuesday to Sunday and until 2000 on Thursdays. Full-price tickets to the gallery including the show cost 12 euros and are available online here (German-language link). The museum is just a few minutes' walk from Friedrichstrasse or Hackescher Markt stations on Berlin's S-Bahn rail network.More Friedrich in the Alte Nationalgalerie

Bang in the middle of the exhibition, on the same top floor of the museum, is the Alte Nationalgalerie's Friedrich gallery, so there's an extra added opportunity to appreciate more paintings by German Romanticism's greatest artist. There are depictions of massive mountains like the Watzmann in the Bavarian Alps, though he never actually saw it in person, and added in rock formations in the foreground from other mountain ranges. And there are other, more intimate paintings, like the Woman at a Window, who both harks back to Dutch genre scenes of the Golden Age and looks forward to Vilhelm Hammershoi almost a century later.Images

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, around 1817, Hamburger Kunsthalle. (c) SHK/Hamburger Kunsthalle/bpk/Elke Walford

Emil Nolde, Winter, 1907, Nolde Stiftung Seebüll. (c) Nolde Stiftung Seebüll

Ivan Nikolayevich Kramskoy, Portrait of Ivan Shishkin, 1873, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. (c) State Tretyakov Gallery

Gustave Courbet, The Meeting or Bonjour Monsieur Courbet, 1854, Musée Fabre, Montpellier. (c) Musée Fabre de Montpellier Méditerranée/Frédéric Jaulmes

Auguste Renoir, Path Leading through Tall Grass, 1876/77, Musée d’Orsay, Paris. (c) Musée d‘Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Patrice SchmidtIvan Nikolayevich Kramskoy, Portrait of Ivan Shishkin, 1873, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. (c) State Tretyakov Gallery

Gustave Courbet, The Meeting or Bonjour Monsieur Courbet, 1854, Musée Fabre, Montpellier. (c) Musée Fabre de Montpellier Méditerranée/Frédéric Jaulmes

Richard Riemerschmid, In the Countryside, 1895, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich. (c) Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau München

Jens Ferdinand Willumsen, A Mountain Climber, 1912, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen. (c) Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018

Comments

Post a Comment