Georges Seurat devised the Neo-Impressionist painting technique popularly known as Pointillism. He didn't live long and left only a small body of work, of which seascapes were a recurring motif; a couple of dozen paintings and drawings from summers spent on the northern coast of France will be brought together for Seurat and the Sea at the Courtauld Gallery in London from February 13 to May 17. Lucian Freud gained recognition as one of the greatest of British portrait painters for his intensely observed works, often of nudes. From February 12 to May 4, the National Portrait Gallery is putting on Lucian Freud: Drawing into Painting , which will be the first exhibition in Britain to focus on his creations on paper, some of which have never been on public display before. Ramses and the Pharaoh's Gold is a travelling exhibition of treasures from Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities: 180 of them, with the coffin of the long-lived Ramses II among highlig...

What a lot of contradictions in Emil Nolde, and in his art.

How could the painter who, more than any other, had his art denounced by the Nazis as degenerate actually be a member of the National Socialist Party? How could a man who professed his Christian values in religious art hold such anti-Semitic views? How could the artist who seemed so at home in the windy, flat farming and fishing country of the German-Danish borderlands be so drawn to the clubs and cabarets of Berlin? And how could the maker of such delicate watercolours also produce violently Expressionist works that were sometimes so crude, so grotesque?

All these questions are raised by Emil Nolde: Colour is Life at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh. Some are answered, but by no means all.

Nolde was born in 1867 as Emil Hansen to a German father and a Danish mother. Nolde is actually the name of the small place he came from, which was then in Germany but became Danish after a plebiscite following World War I, and he adopted it as a surname after he married in 1902. He trained as a wood sculptor and draughtsman and turned to painting relatively late, in the mid-1890s.

Here he is, in a Self-Portrait at the age of 50, in one of the first pictures you see in a room devoted to works from his Heimat -- a German word translated as home or homeland but with far more emotive connotations than either of those English equivalents. The dazzling azure eyes stare out at you piercingly from amid the thickly applied paint.

Like virtually all of the pictures in this exhibition, this one comes from the Nolde Foundation, housed in a residence he himself designed in 1927 in Seebüll, just on the German side of the new border with Denmark. Many of the early works are of the local landscape, gardens and the close-knit community, to which Nolde felt a strong attachment.

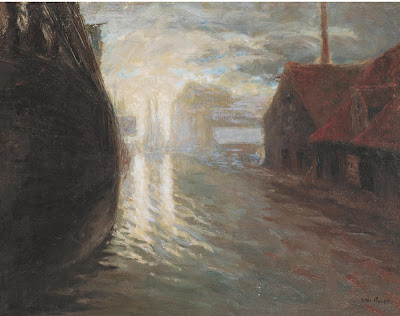

Even though Nolde was entitled to -- and took up -- Danish citizenship when his birthplace changed country, he felt himself very much a German. However, this 1902 picture, of a canal in Copenhagen, has perhaps something of the Dane about it, its muted tones reminiscent of Vilhelm Hammershoi.

But this work is by no means typical. Nolde was soon to unleash bursts of colour on the world. He and his wife, Ada Vilstrup, a Danish actress and dancer, would spend their first summers after their marriage on the island of Als (then German, now Danish -- it gets quite confusing). It was then he began to emphasise individual colours for expressive and emotional effect. Milkmaids I is an early example of this rural Expressionism, dating from 1903, with that corn-yellow sky framing the heads of two of the women.

Some of the pictures in this section are striking. Dr H from 1910 wears a startling red beard, while Trollhoi's Garden, from 1907, is a mosaic of reds, blues, yellows and greens. Four years into World War I, Blonde Girls, again pictured among flowers, seems unbelievably bright and cheerful for such a period.

The paintings of this era weren't always so carefree. As war approached in 1913, Nolde produced Soldiers, depicting serried ranks of dark-blue clad, red-faced troops in spiked helmets with rifles and bayonets. Bleaker still is the very disturbing Battlefield, at its centre a rearing, bulging-eyed horse.

From 1904, Nolde usually spent the summers in the borderlands but the winters in Berlin, where the nightlife drew his attention and he sought to capture all the movement and energy of the dancers and the clientele. The watercolours he made have a restrained simplicity, while still encapsulating the vivacity of the moment. The oils, on the other hand, are very intense, with caricatured faces and broad brushstrokes, coming to life best when seen from a distance. Party from 1911 is typical.

There's more energy in this same room in a series of works depicting the port of Hamburg in 1910, with Nolde's use of a brush and ink resembling Asian art or calligraphy. The boats themselves are blurs of motion.

And then it's on to the religious pictures. "Anything can be painted as long as it lies within the possibilities of colour," Nolde said. What about Ecstasy, though? It's Mary, presumably, at the moment of conception, stark naked, leaning back, long black hair, blue eyes bulging, red lips open. Orgasmic rather than immaculate, it seems. In the background is another woman, orange-haired, holding up a turquoise cross.

Paradise Lost is another astonishing image. Adam and Eve sit in the foreground, divided by the evil-looking green serpent slithering up the purple tree between them. Adam merely looks somewhat cheesed off, but Eve's bright blue eyes stare vacantly, despondently, inconsolably past us into the distance.

Nolde wanted to grab you by the throat and assault the senses with his expression on canvas of the depth of his religious conviction. Martyrdom, from 1921, was painted on sackcloth with deliberately grotesque forms and sensational colours. But the caricatured Jewish faces in the foreground almost block out the figure of Christ on the cross.

This is where it gets very uncomfortable. Nolde expressed anti-Semitic opinions about Jewish artists, including Max Liebermann, perhaps Germany's most distinguished Impressionist, whose work he denounced as "weak and kitsch". Despite his views, and despite his party membership and enthusiastic support for Hitler, Nolde found his work as despised by the Nazis as that of other Expressionists. More so in fact. More than 1,050 of his works were removed from display, the most of any artist, and he also had more works than anyone else -- 33 -- included in the 1937 Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich.

As a result, Nolde found it difficult to obtain oil paint and canvases, so he switched largely to watercolours, which he hoped to turn into oils later. In the final room, there are a lot of these "unpainted pictures", but more interesting are vibrant seascapes, as well as some striking late works, including Large Poppies (Red, Red, Red), astonishingly from 1942, at the height of World War II.

In this show, you'll find out a lot about a complex and rather conflicted painter who produced some highly challenging art, some of it terrific, some of it fairly horrible. But however much you admire some of the pictures, it appears very difficult to like Nolde the man.

Emil Nolde, Canal (Copenhagen) (Kanal (Kopenhagen)), 1902. © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll

How could the painter who, more than any other, had his art denounced by the Nazis as degenerate actually be a member of the National Socialist Party? How could a man who professed his Christian values in religious art hold such anti-Semitic views? How could the artist who seemed so at home in the windy, flat farming and fishing country of the German-Danish borderlands be so drawn to the clubs and cabarets of Berlin? And how could the maker of such delicate watercolours also produce violently Expressionist works that were sometimes so crude, so grotesque?

All these questions are raised by Emil Nolde: Colour is Life at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh. Some are answered, but by no means all.

Nolde was born in 1867 as Emil Hansen to a German father and a Danish mother. Nolde is actually the name of the small place he came from, which was then in Germany but became Danish after a plebiscite following World War I, and he adopted it as a surname after he married in 1902. He trained as a wood sculptor and draughtsman and turned to painting relatively late, in the mid-1890s.

Here he is, in a Self-Portrait at the age of 50, in one of the first pictures you see in a room devoted to works from his Heimat -- a German word translated as home or homeland but with far more emotive connotations than either of those English equivalents. The dazzling azure eyes stare out at you piercingly from amid the thickly applied paint.

Like virtually all of the pictures in this exhibition, this one comes from the Nolde Foundation, housed in a residence he himself designed in 1927 in Seebüll, just on the German side of the new border with Denmark. Many of the early works are of the local landscape, gardens and the close-knit community, to which Nolde felt a strong attachment.

Even though Nolde was entitled to -- and took up -- Danish citizenship when his birthplace changed country, he felt himself very much a German. However, this 1902 picture, of a canal in Copenhagen, has perhaps something of the Dane about it, its muted tones reminiscent of Vilhelm Hammershoi.

But this work is by no means typical. Nolde was soon to unleash bursts of colour on the world. He and his wife, Ada Vilstrup, a Danish actress and dancer, would spend their first summers after their marriage on the island of Als (then German, now Danish -- it gets quite confusing). It was then he began to emphasise individual colours for expressive and emotional effect. Milkmaids I is an early example of this rural Expressionism, dating from 1903, with that corn-yellow sky framing the heads of two of the women.

Some of the pictures in this section are striking. Dr H from 1910 wears a startling red beard, while Trollhoi's Garden, from 1907, is a mosaic of reds, blues, yellows and greens. Four years into World War I, Blonde Girls, again pictured among flowers, seems unbelievably bright and cheerful for such a period.

The paintings of this era weren't always so carefree. As war approached in 1913, Nolde produced Soldiers, depicting serried ranks of dark-blue clad, red-faced troops in spiked helmets with rifles and bayonets. Bleaker still is the very disturbing Battlefield, at its centre a rearing, bulging-eyed horse.

From 1904, Nolde usually spent the summers in the borderlands but the winters in Berlin, where the nightlife drew his attention and he sought to capture all the movement and energy of the dancers and the clientele. The watercolours he made have a restrained simplicity, while still encapsulating the vivacity of the moment. The oils, on the other hand, are very intense, with caricatured faces and broad brushstrokes, coming to life best when seen from a distance. Party from 1911 is typical.

There's more energy in this same room in a series of works depicting the port of Hamburg in 1910, with Nolde's use of a brush and ink resembling Asian art or calligraphy. The boats themselves are blurs of motion.

And then it's on to the religious pictures. "Anything can be painted as long as it lies within the possibilities of colour," Nolde said. What about Ecstasy, though? It's Mary, presumably, at the moment of conception, stark naked, leaning back, long black hair, blue eyes bulging, red lips open. Orgasmic rather than immaculate, it seems. In the background is another woman, orange-haired, holding up a turquoise cross.

Paradise Lost is another astonishing image. Adam and Eve sit in the foreground, divided by the evil-looking green serpent slithering up the purple tree between them. Adam merely looks somewhat cheesed off, but Eve's bright blue eyes stare vacantly, despondently, inconsolably past us into the distance.

Nolde wanted to grab you by the throat and assault the senses with his expression on canvas of the depth of his religious conviction. Martyrdom, from 1921, was painted on sackcloth with deliberately grotesque forms and sensational colours. But the caricatured Jewish faces in the foreground almost block out the figure of Christ on the cross.

This is where it gets very uncomfortable. Nolde expressed anti-Semitic opinions about Jewish artists, including Max Liebermann, perhaps Germany's most distinguished Impressionist, whose work he denounced as "weak and kitsch". Despite his views, and despite his party membership and enthusiastic support for Hitler, Nolde found his work as despised by the Nazis as that of other Expressionists. More so in fact. More than 1,050 of his works were removed from display, the most of any artist, and he also had more works than anyone else -- 33 -- included in the 1937 Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich.

As a result, Nolde found it difficult to obtain oil paint and canvases, so he switched largely to watercolours, which he hoped to turn into oils later. In the final room, there are a lot of these "unpainted pictures", but more interesting are vibrant seascapes, as well as some striking late works, including Large Poppies (Red, Red, Red), astonishingly from 1942, at the height of World War II.

In this show, you'll find out a lot about a complex and rather conflicted painter who produced some highly challenging art, some of it terrific, some of it fairly horrible. But however much you admire some of the pictures, it appears very difficult to like Nolde the man.

Practicalities

Emil Nolde: Colour is Life is on at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (Modern Two) in Edinburgh until October 21. It's open daily from 1000 to 1700 and full-price tickets cost £10. Tickets can be bought online here. The gallery is on Belford Rd to the west of the city centre. It's 15 minutes' walk from Haymarket Station, or there are buses from Waverley Station and Princes St.Images

Emil Nolde, Self-Portrait (Selbstbild), 1917. © Nolde Stiftung SeebüllEmil Nolde, Canal (Copenhagen) (Kanal (Kopenhagen)), 1902. © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll

Emil Nolde, Milkmaids I (Melkmädchen I), 1903. © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll

Emil Nolde, Party (Gesellschaft), 1911. © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll

Emil Nolde, Large Poppies (Red, Red, Red), (Grosser Mohn (Rot, Rot, Rot)), 1942. © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll

Comments

Post a Comment